Proof by Construction: Building a Mathematician's Assistant

What do you do after interviewing so many mathematicians to understand how their practice is evolving? After listening to them describe the newly discovered tools they have come to love1, alongside their long-standing frustrations?

Base Case: My Mathematical Trajectory

I could not help feeling that my professional trajectory was finally starting to make sense. I began as an apprentice mathematician, playing with commutative diagrams and categorification. Later, I joined a data analytics company called Dataiku, an early startup at the time, back in 2015, whose product was an end-to-end collaborative platform designed to democratize access to machine learning.

My role there was to turn projects with significant scientific uncertainty but clear business potential into actionable product features. The first initiative focused on optimizing data labeling (through active learning cardinal mainly) while the last revolved around causal inference.

In retrospect, this placed me at the perfect intersection: a deep understanding of, and empathy for, mathematicians on the one hand, and hands-on experience building software products on the other.

It began to feel almost obvious that I should try to build tools for mathematicians. What follows is the first stab at this idea: a prototype, not a finished product. It’s a story of experimentation, of iterating through ideas and learning from missteps, rather than delivering polished features. The app described here is very much a work in progress, designed to explore what building supportive tools for mathematicians could even look like, and to gather feedback that will guide its evolution.

Induction on Features: Initialization

Just as one explores a mathematical statement through its first nontrivial example, a product should begin with one—and only one—feature. Since AI-assisted proving was (and still is) very much in vogue, the initial task was to design the smoothest possible user experience for proving something collaboratively with an AI model.

The #1 pain point that consistently resurfaced in discussions with mathematicians was the iteration process itself. Once a correction is requested, the system regenerates an entirely new proof, with no guarantees that other parts have not been silently altered. The result is an experience that is simultaneously token-wasteful and deeply frustrating.

Often a simple mistake (a wrong sign, a forgotten term,…) would slip into the AI’s output amidst an otherwise genuine helpful proof. Such errors would be immediately forgiven if made by a human, but not by an AI. Once again, the mathematician must point out the mistake, only for the model to stumble and generate excuses… before producing an entirely new proof from scratch.

To address these issues, we can take two complementary approaches:

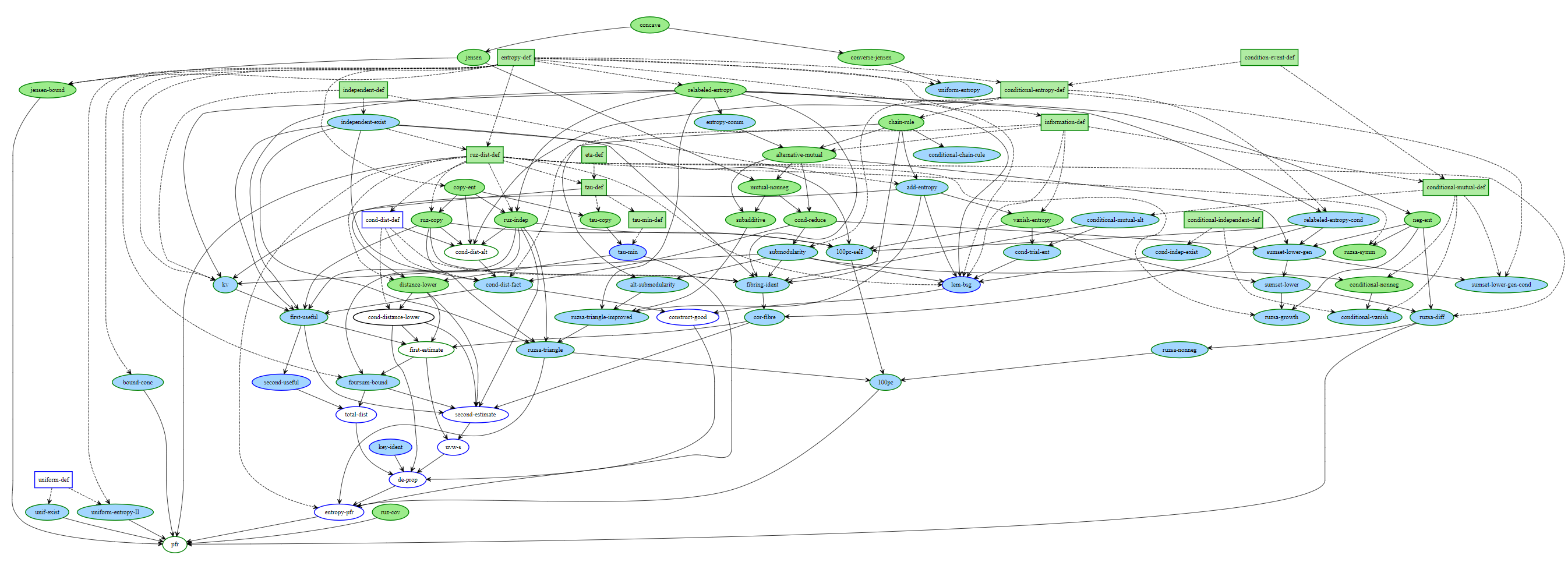

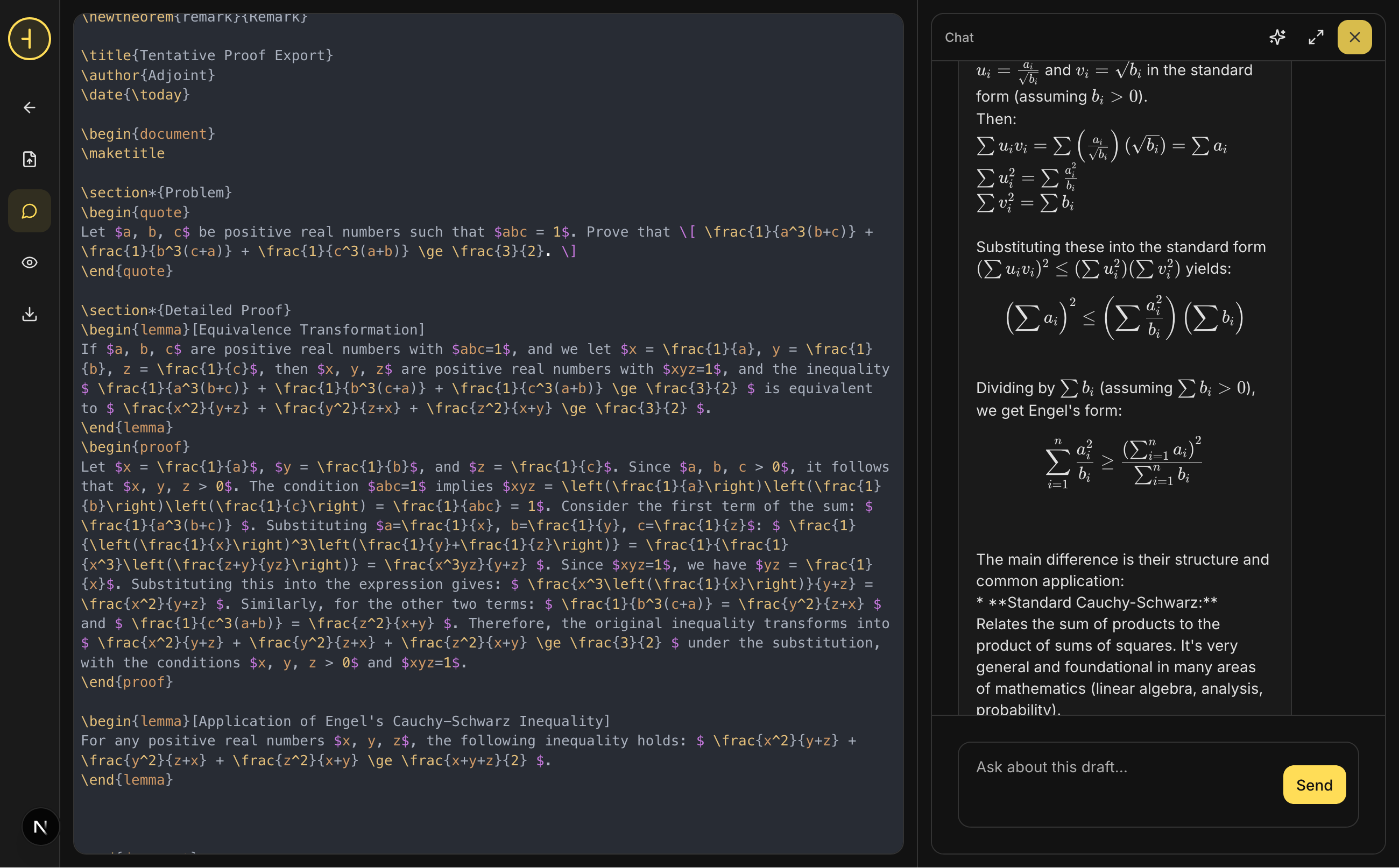

- Decompose the proof attempt into intermediate results, lemmas, together with their logical dependency graph, so that we can ask for modification of one component without altering the others.

- Allow direct intervention, letting the mathematician edit the proof attempt directly. Similar to Claude’s canvas feature, for instance].

This first decomposition can be achieved with a dedicated AI model and the right prompting: it takes the original proof attempt from the first model and outputs the lemmas along with its associated dependency graph. We could call this process blueprint inference, analogous to generating a “blueprint” in Lean.

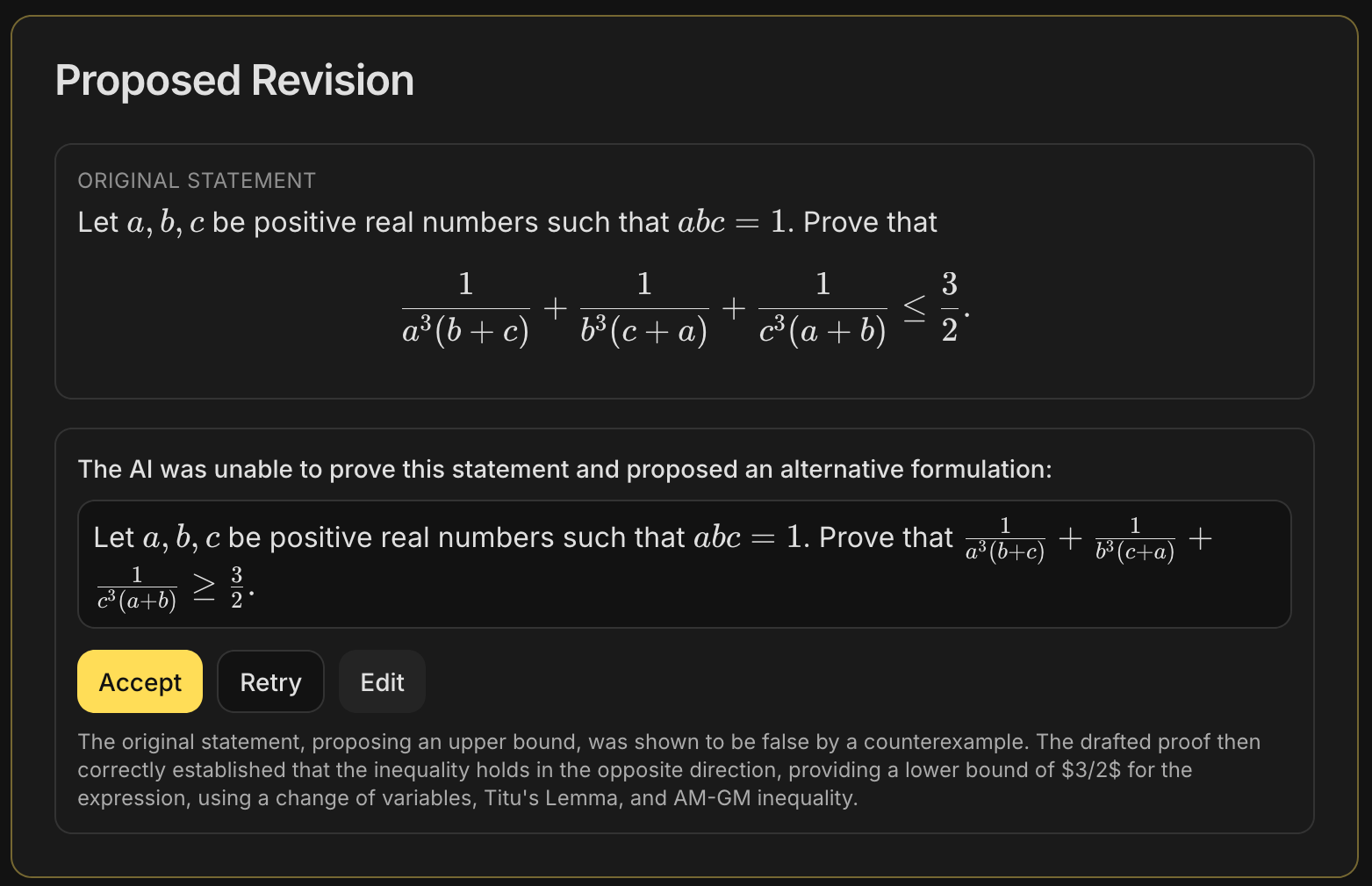

Wait, what if the statement… is false in the first place?

In the unlikely event that a mathematician submits a false statement and asks an AI model to prove it, what happens? The system doesn’t necessarily break, but it must clearly notify the user that the direction has changed. This is especially important because mathematicians may sincerely believe the statement to be true, and the prover model itself could be mistaken.

A recent study by researchers at INSAIT and ETH Zurich introduced BrokenMath2. The benchmark was designed to measure this sycophancy phenomenon in AI models.

To detect it, we run a first LLM over the original proof attempt to determine whether the statement has been proved, disproved, or if nothing conclusive has been established.

Wait, what if there is no statement to be proved… in the first place?!

As extensively argued in previous posts, proving is only a small fraction of a mathematician’s activity. Mathematicians also use AI models for a variety of exploratory tasks. A natural extension of proving is exploration: starting from a half-baked statement or an open question, the mathematician begins a discussion that may eventually yield statements worth proving or disproving.

This changes the nature of the initial input to the app. There should be two modes: explore and prove, with smooth transitions between them. In this context, the chat interface is the natural candidate for exploration, enabling dialogue with the AI model. But, as before, chat is not the end point. We enhance the interaction by constantly scanning for the linguistic components of the mathematical discourse (statements, hypotheses, or examples) so that attempting a proof is always just a click away.

Interfaces, Models, and Hidden Assumptions

With the feature set and interaction modes in place, it’s worth stepping back to examine some broader design considerations. How we structure interfaces, integrate AI models, and account for hidden assumptions fundamentally shaped the product.

Is every interface converging to a chat? On one hand, the chat interface is simple, versatile, and almost Zen in its minimalism. On the other hand, as the de facto default in a post-ChatGPT world, it can feel lazy and unfocused. As noted earlier regarding iteration, relying on chat as the alpha and omega of the user interface often comes with significant drawbacks.

In proving mode, chat is a second-class citizen. There are more natural ways to interact with and iterate on a tentative proof whether through direct user edits or by asking an AI model to check a lemma or any smaller substatement. Chat remains available for more open-ended questions and broader modifications. Crucially, every model output is analyzed by yet another LLM to determine its impact on the proof and to propose updates directly within the structured proof itself.

Model-agnostic by design. A deliberate choice in this project was to rely almost entirely on the capabilities of existing AI models, rather than training bespoke prover models or building heavy scaffolding3. This was not a technical limitation, but a product decision.

The pace of progress in foundation models makes tightly coupled architectures brittle: elaborate pipelines risk becoming obsolete with each major release. By contrast, a thin, model-agnostic layer that focuses on interaction, structure, and user control is more likely to age well.

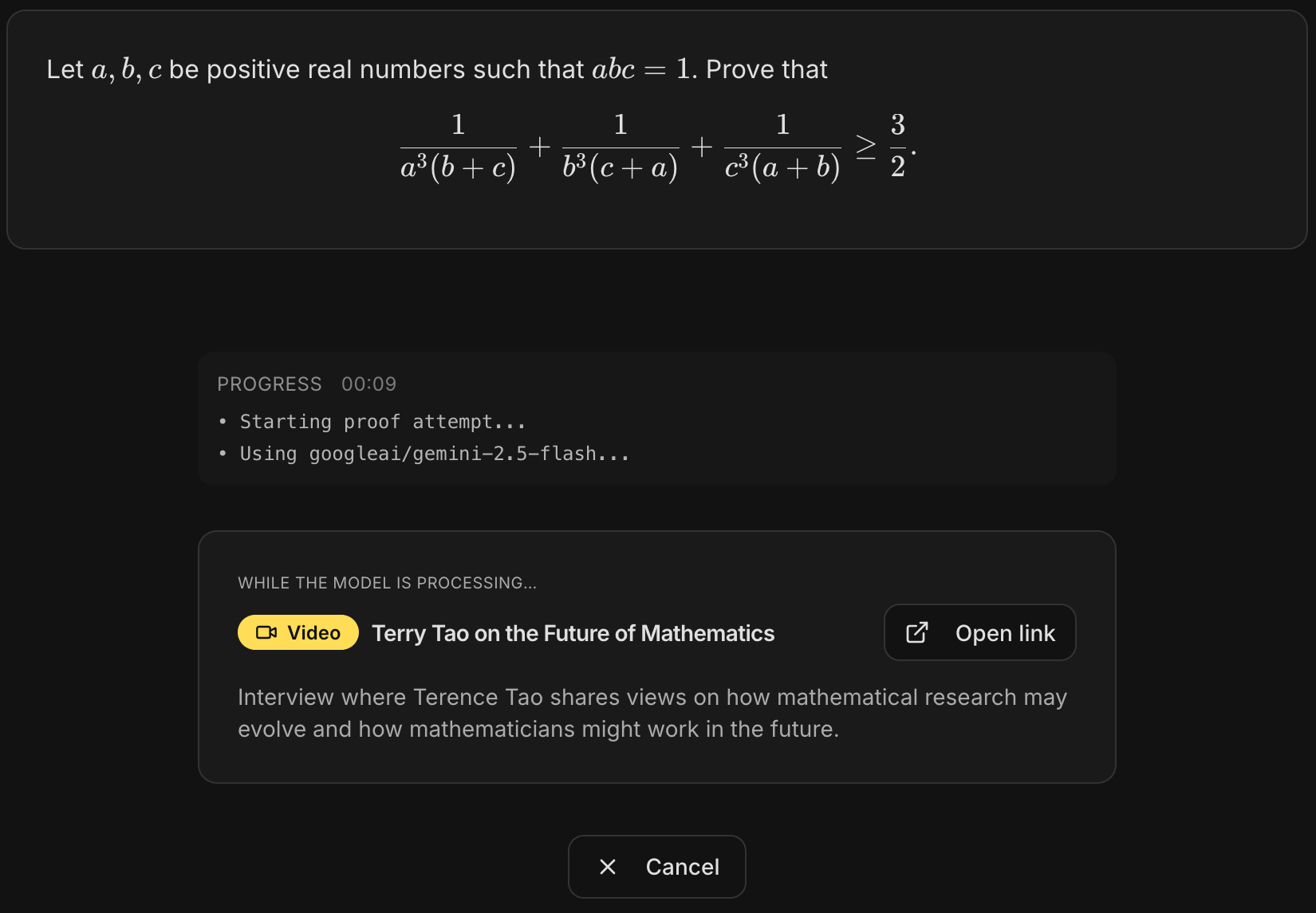

Latency as a feature. A practical consequence of leaning on powerful, general-purpose models is latency. Some operations can take more than several minutes. We chose to make it a first-class part of the user experience by surfacing content designed to keep the mathematician engaged: short mathematical digressions, alternative viewpoints on the topic at hand curated from a growing collection of high-quality AI-generated mathematical trivia.

Hidden Assumption. The first feedback session with a mathematician design partner quickly surfaced a subtle but important assumption embedded in the prototype. The system had been implicitly designed to help mathematicians understand and validate existing statements, often results that were already known to be true but worth re-deriving or unpacking. It was much less suited to helping them formulate and develop their own statements from scratch.

This is a textbook example of hidden product bias, it reinforced a familiar lesson—nothing accelerates product iteration quite like candid, early user feedback.

Addressing this gap led to the introduction of a new interaction mode, centered around a different primitive: a workspace. It is deliberately unassuming, just a plain text editor, but one augmented with lightweight, context-aware actions. Any fragment of text can be sent for proving attempt.

Crucially, the workspace is not isolated. Partial results, proof attempts, and exploratory discussions from both prove and explore modes can be pulled back into it.

Introducing The Adjoint

Mal nommer les choses c’est ajouter au malheur du monde

After building all of the above, we needed a name for what we had started creating. This is when the above quote came to mind. Usually attributed to Albert Camus, it was also one of the most powerful lessons I received from one of my PhD advisors, Michel Broué. So what mathematical term could also describe a mathematician’s assistant? The adjoint, of course.

And for inasmuch as the models we rely on are occasionally forgetful, the adjoint is free4 and open source!

What’s next?

This is a first prototype to start and collect feedback. It’s rough around the edges and there are still many features to add. Validation of lemmas and local statements with symbolic engines such as Sympy or with formal languages such as Lean or Rocq, running numerical experiments in Python, or a proper literature search. Ah and of course, there is always some improvement to be made on robust display of LaTeX, but we might have to wait for AGI to finally fix that…

In the meantime, you can share your ideas and contribute on github to help shape your Adjoint.

Updating the Prior

Following the initial release, and thanks to extensive early feedback from both mathematicians and product engineers, several design flaws became clear. In particular, the separation between Explore, Prove, and Write created unnecessary cognitive overhead and obscured their underlying continuity.

The product has since converged toward a single, unifying primitive: the workspace. From this shared space, mathematicians can draft notes, explore ideas via chat, and ask an AI to attempt proofs, with results flowing naturally back into their working document.

Encouragingly, this direction aligns closely with the recent release of OpenAI’s Prism, which independently arrives at a similarly workspace-centered model.

-

Perhaps not the most precise name for the benchmark, since it is the models —not the mathematics— that are “broken”; naming things is hard… ↩

-

Such as Winning Gold at IMO 2025 with a Model-Agnostic Verification-and-Refinement Pipeline or Tobias Osborne’s Alethfeld. ↩

-

Hope everyone got my categorical pun… ↩