Assistants of Abstraction: Proofs & Machines

The age-old tale of technology replacing human workers is playing out once again. Only this time, it’s on speakerphone, stuck on repeat and the technology is Artificial Intelligence. First, we said it would alleviate us from boring, mundane, repetitive tasks like processing invoices in accounting, reviewing legal documents for keywords, or transcribing meeting notes in admin roles. Then Stable Diffusion came along, and suddenly AI started staking its claim on creativity 1. A few months later, ChatGPT was released.

Then the unthinkable happened: Science itself was swept up in the AI revolution. In July 2024, DeepMind’s AlphaProof took home the silver medal at the International Mathematical Olympiad. By October, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded — not just to chemists, but also to computer scientists at DeepMind, again. A creeping cynicism seems inevitable — because if even science can be automated, what remains sacred?

As a mathematician-turned-AI practitioner myself, I couldn’t stay untouched by this whole movement. And yet, something felt off. While the impact on chemistry was undeniable, AI is still nowhere near earning a Fields Medal. Solving IMO problems might be impressive (and not just for AI), it remains largely symbolic. It’s a far cry from making a real impact on working mathematicians. This is a first sign of the cultural divide between the AI and the mathematics community2.

For instance, the pride of AI scientists is to show “sota results”3 on any benchmark. What does it actually translate to, if anything? No one knows, no one cares. What does it mean for a mathematician that the latest LLM can solve k out of n problems from a competition? Nothing. Most of the mathematician endeavour is not to prove a theorem, but to state it. And even when the question is already well-posed, it’s quite far from competitive math problems.

All benchmarks are bad, some are useful ¯_(ツ)_/¯

In search for AGI, or simply recoginition and fundings, the ML community is chasing benchmarks after benchmarks. And like every experimental sciences, it suffers from the many ills of the reproducibility crisis, where poor rigor sometimes flirts with intellectual dishonesty. On top of which we have to add that most of top research labs are privately owned and have no incentives to build open science.

In a post-LLM world where models are constantly trained on the Internet, the integrity of benchmarks is even more at risk. This is the contamination plea which shows once again the limits of relying on benchmarks to validate models performance and their applicability to the real world. Perhaps the only notable exception to that was the arcAGI initiative.

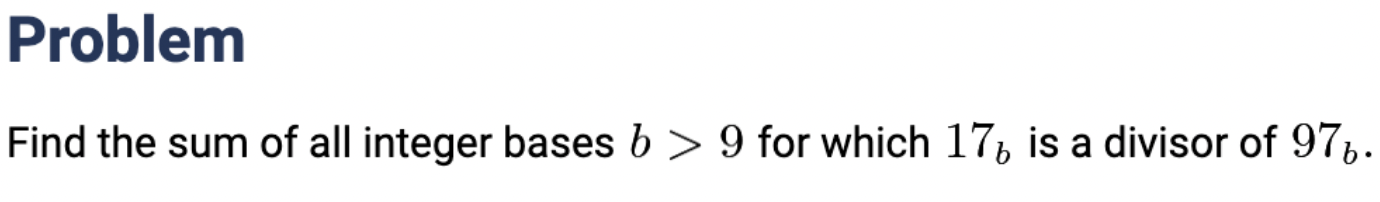

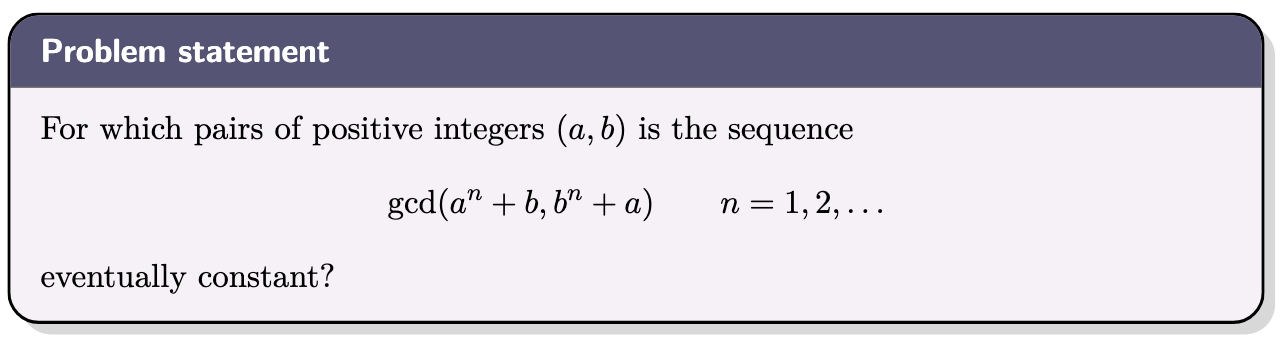

To fight against data contamination, MathArena proposes to only test LLMs on newly math competitions that are published after the models initial releases. The original enthusiasm for this new approach was seriously reduced after it was shown that some of the problems for AIME 2025 already existed on the Internet so that LLMs might very well have been trained on those like the very first problem of AIME 2025:

|

|

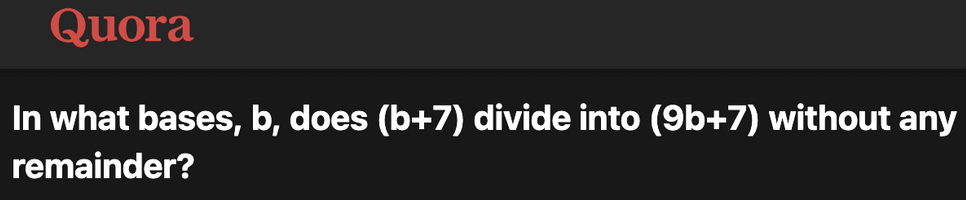

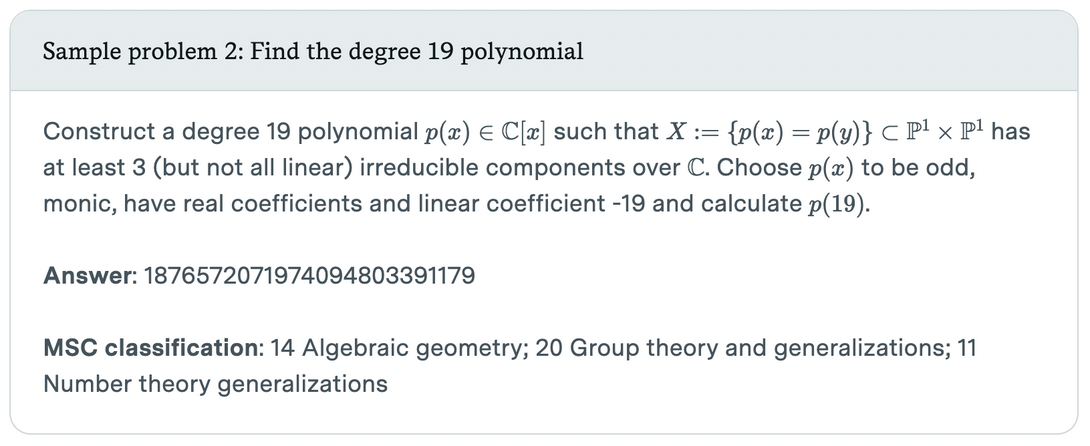

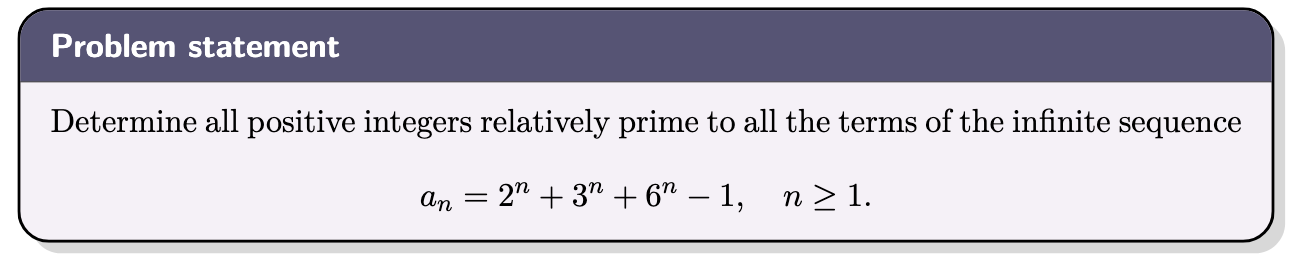

Trying to escape the limitation of high-school mathematics, FrontierMath presented itself as a more realistic research-level mathematic benchmark. If the selected problems are indeed rooted in research-level mathematics, they constrained the answers to always be numerical which yields to the strangest of statements that can only make a mathematician smile (or cry4).

Worst perhaps, as to add insult to the injury, it was later revealed that the benchmark was compromised by being funded by openAI in exchange for early access… without being properly advertised.

Not only those benchmarks have no direct impact for mathematicians, but they offer very limited robust insights for AI scientists to advance the fields.

The Future of Proof: AI and the Formalization Revolution

But there is hope beyond broken benchmarks. There are reasons to believe AI could actually change the course of mathematics. However this revolution cannot come from LLMs alone but from its fruiftul mariage with formal languages.

At the heart of Mathematics lies two dual forces: intuition and formalization. Formalization in its common sense is making rigorous what our intuitions tells us: it converts an idea into a proof. But as long as this is constrained by the expression of our language, this process can only be imperfect. There are countless examples of famous mathematicians publishing errors whether Henri Poincaré on the three-body problem or Field medalist Vladimir Voevodsky that upon discovering errors in his work became deeply interested in the foundations of mathematics which led him to develop homotopy type theory as a new conceptual framework that also influenced the design of formal languages in some proof assistants. The only way to get true absolute formalization with guarantees is through the use of proof assistant languagues such as Lean, Rocq or Isabelle that gives formalization guarantees.

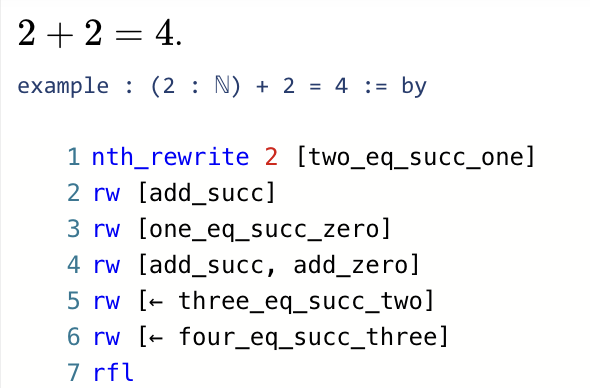

Proving that 2 + 2 = 4 in a formal language becomes slightly cumbersome as it reveals all the hidden steps that we always skip to justify it properly.

It’s a nice example of the so-called De Bruijn factor which is the measure of the effort to convert an informal proof into a formal proof whose proxy unit is the ratio of proof length. If it can vary from 5 to 80 (according to this). The more theory is needed to state a definition or theorem, the more work there is. If there are librairies, such as mathlib in Lean, to centralize the developement of formalized statements to build on top of, it still represents just a tiny portion of all (informal) mathematics5.

The latest and hottest formalization project is The Fermat’s last theorem project which was planned to last for at least 5 years. The gap from informal to formal mathematics is vast. The body of formal mathematics is minuscule compared to the vast expanse of informal mathematics.

This is where AI can truly shine and help alleviate the complex endeavour of formalization while offering a possibility for scaling. After all, with enough (informal, formal) paired data, one can hope that AI could help translate from one to the other.

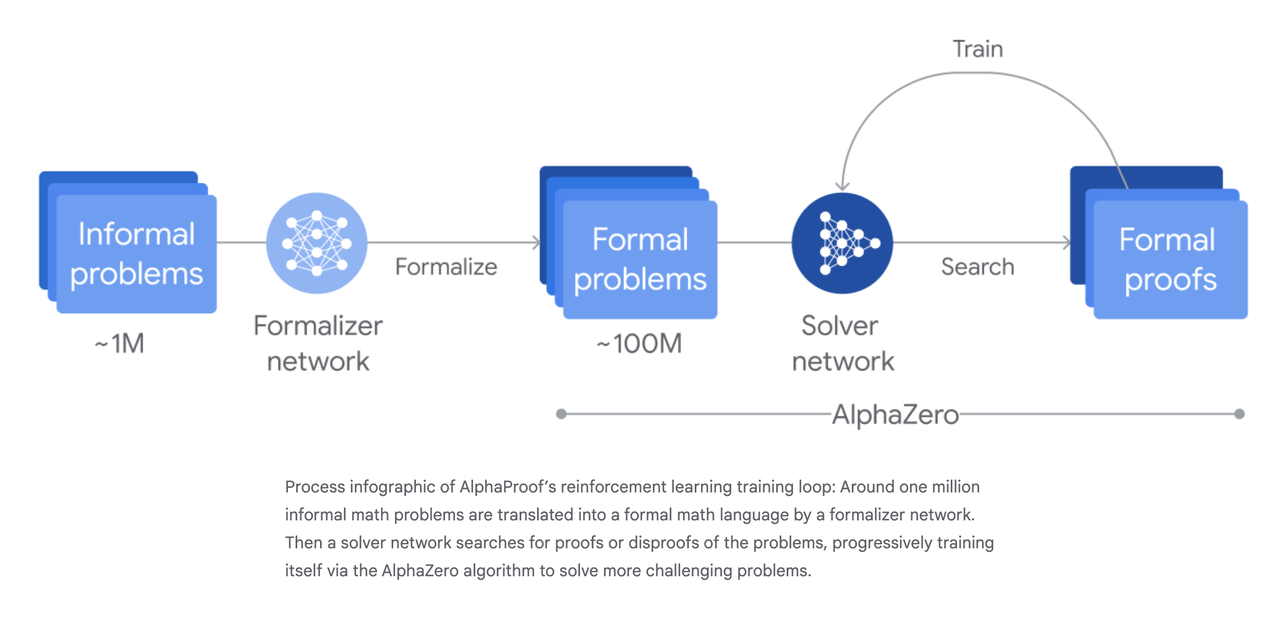

Conversely, in order to successfully build systems that can solve mathematics problems, IMO or not, AI models needed formal languages for validation. There is no point in training sophisticated prover models on millions of problems if we can’t tell how well they perform (instantly). When DeepMind announced AlphaProof, the first AI system to achieve a silver medal at the IMO6, it relied on two main components:

- Autoformalization of informal statements.

- Automated proving in Lean space.

As much as AlphaProof was an undeniable breakthrough in the world of AI, it had more than a limited impact in the world of mathematics.

Bridging the Gap from Informal to Formal Mathematics

Even if AI models can prove complex results, they might not be aligned with mathematical informal human proofs. Kevin Buzzard explain this very cleary in his blogpost:

We would like to see “prove this theorem, correctly, and explain what makes the proof work in a way which we humans understand”.

With the language model approach I worry (a lot) about “correctly” and with the theorem prover approach I worry about “in a way which we humans understand”.

Aligning informal and formal mathematics is harder than simply translating from one language to another sentence by sentence7.

First, there is no clear relationship between the number of informal and formal logical steps . As we saw earlier, an elementary step in informal mathematics (e.g., 2+2=4) requires significantly more steps in Lean when done from first principles. On the other hand, just like any programming language, much of the heavy lifting of a mathematical proof can sometime be encapsulated in one tactic (like the ring or simp tactic).

Formalization often requires subjective decisions. Some became standards, like the notion of limits in calculus. While every math student has been introduced to the classic ε–δ definition of limits, mathlib use Bourbaki’s more general notion of filters (see here).

Another example of complex tranlation behavior is given by the innoncent sum of the first n integers 1+...+n. It is equal to n*(n+1)/2 but its proof in Lean becomes considerably easier if it is transformed to 2(1+...n) = n*(n+1). Even the choice of variable types in Lean can be ambivalent so that a positive natural integer n can be translated into n : ℕ+ or (n : ℕ) (h : 0 < n) (see the suggested IMO Lean formalization conventions).

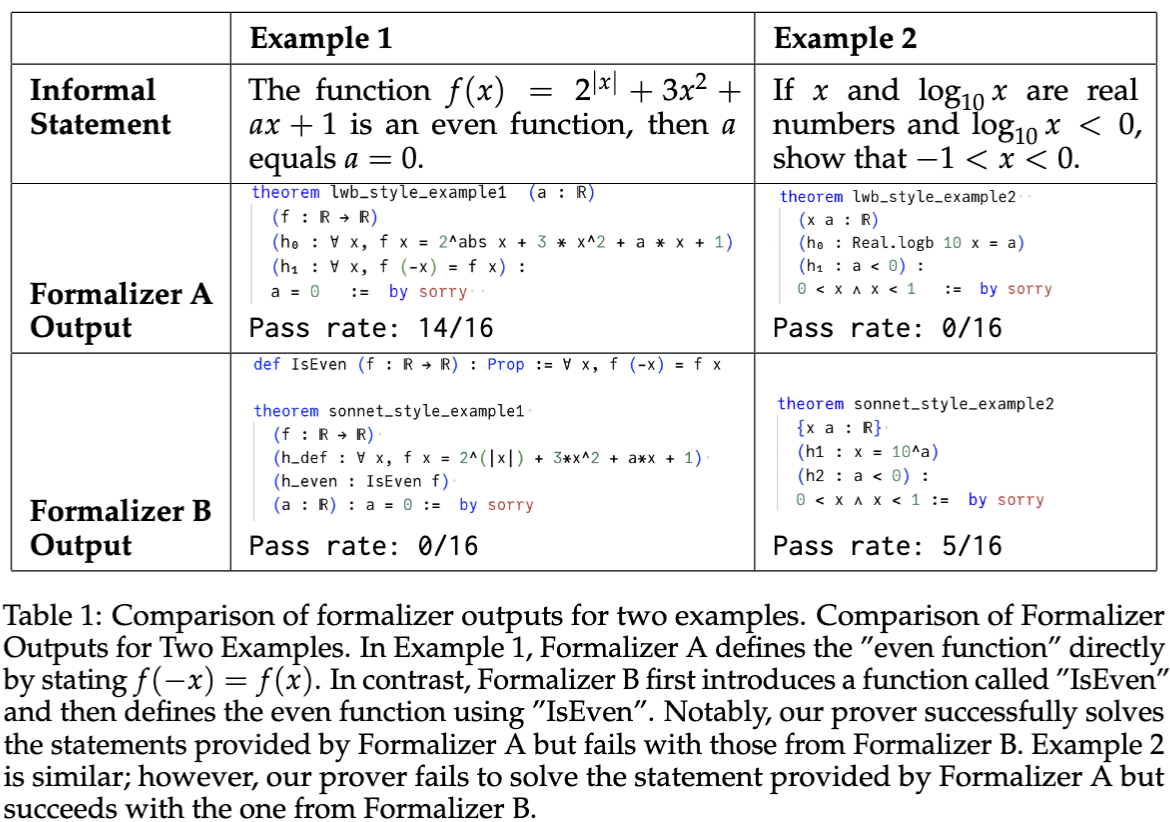

Finally, the formalised version of an informal statement can have an impact on the capacity of AI prover models to prove the statement

There is two avenues to address this informal/formal discrepancy:

- post-process valid formal proofs into more adequate mathematician-like proofs to make it more concise or readable. That’s what work like ImProver have started to explore for formal proofs. On top of which one could apply informalization, i.e. translating it into informal proof8.

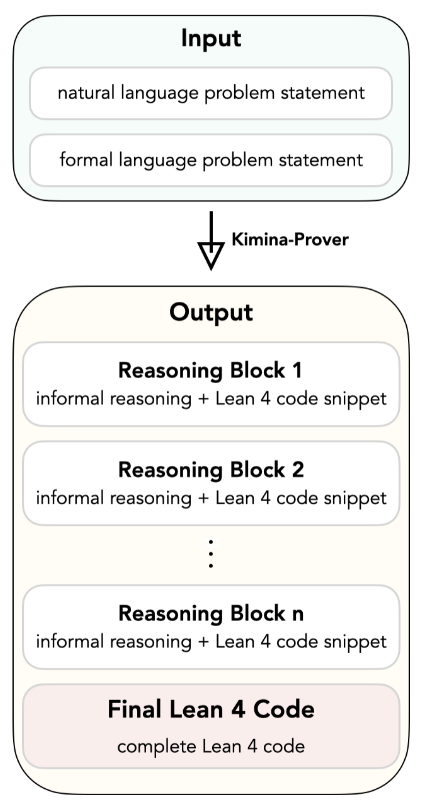

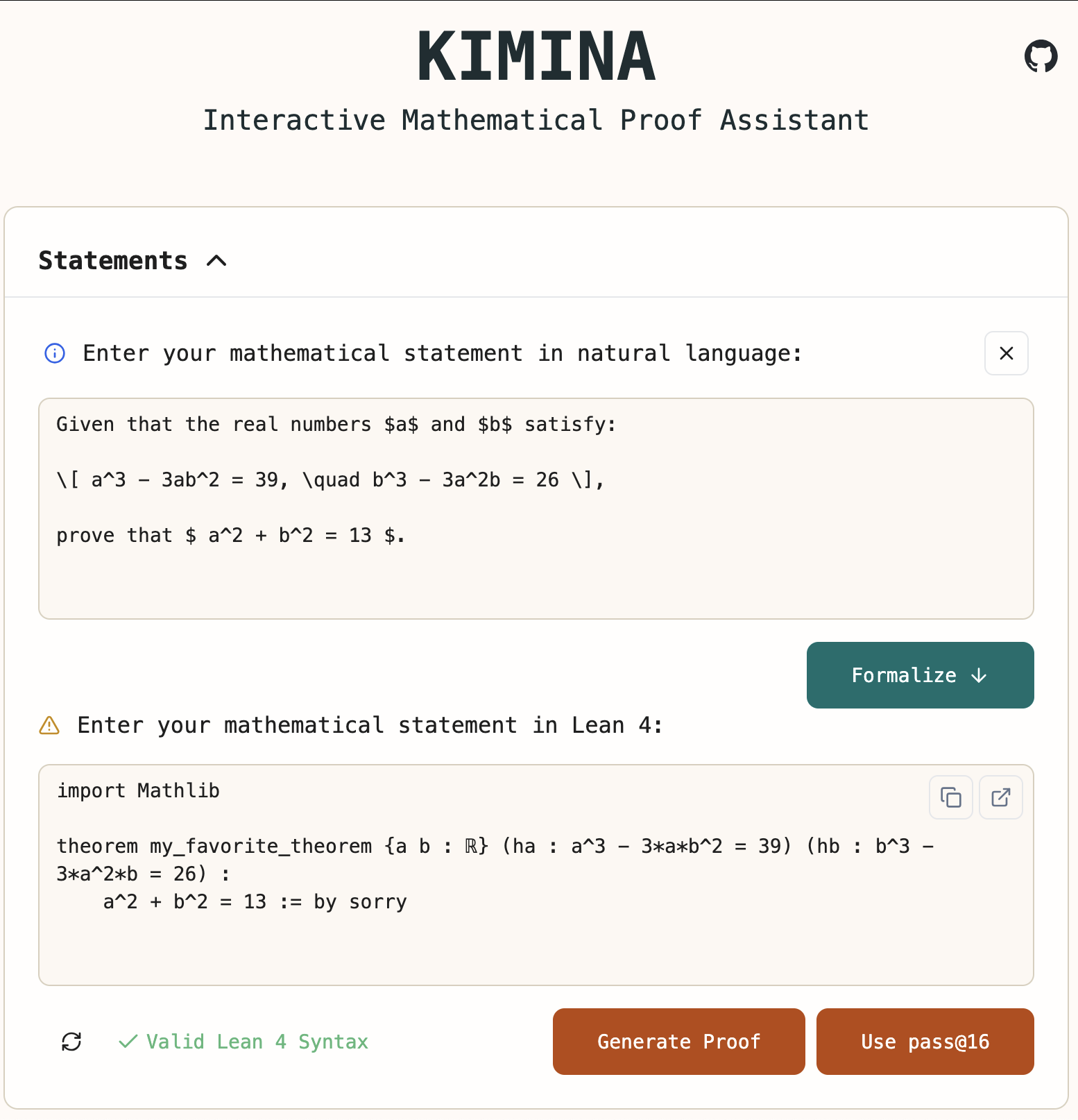

- force the theorem provers model to generate natural proofs. This is what Kimina-Prover9 set up to do by following the DeepSeek-R1 recipe of long chain-of-thoughts. Specifically, the model is trained to “think” (literally between

You can interact with Kimina-Prover and take it for a spin on your favorite IMO-level problem here.

We Want More Than Proof: Aligning AI with Human Mathematics

Perhaps the ultimate sign of the misalignement between the two worlds is that the first cares for proving problem while the second cares for understanding them. AlphaProof can prove problem P2 of the 2024 IMO, but it’s arguably more interesting to know that it could be solved using the same technique as problem P4 of the 2005 edition (see Evan Chen’s full solutions to get the common hint to the two problems).

The limitation of AI benchmarks, where models can exploit similarities between their training data and the benchmark data, is exactly what mathematicians aim for: finding similar problems, equations or formulaes than the ones they are currently facing. In Machine Learning terms, this is simply mathematical semantic search which is often referred to as Mathematical Information Retrieval (MIR)10. The need for mathematical knowledge management has been clearly expressed by the community for a few decade already.

Trading the ambivalence of natural language for Mathematics comes with its unique set of challenges, whether notation ambiguity (G denotes a group or a graph?), non-trivial semantic equivalences (n*(n+1)/2 or ∑_{i=1}^n i?) or even symbolic sensitivity (semantic impact of a change of sign). Those are fundamental limitations for building efficient indexing systems for Mathematics that might explain why current specialised search engines such as approach.xyz or searchonmath are still far from being satisfactory.

As a quick experiment, querying general-purpose commercial LLMs to recognize group structures, such as G=⟨a,b ∣ a^2=b^2=(ab)2=e⟩, yields inconsistent yet promising results(Claude succeeds immediately, while ChatGPT typically fails but can self-correct with ease). This is an encouraging sign that LLMs could help with this retrieval task.

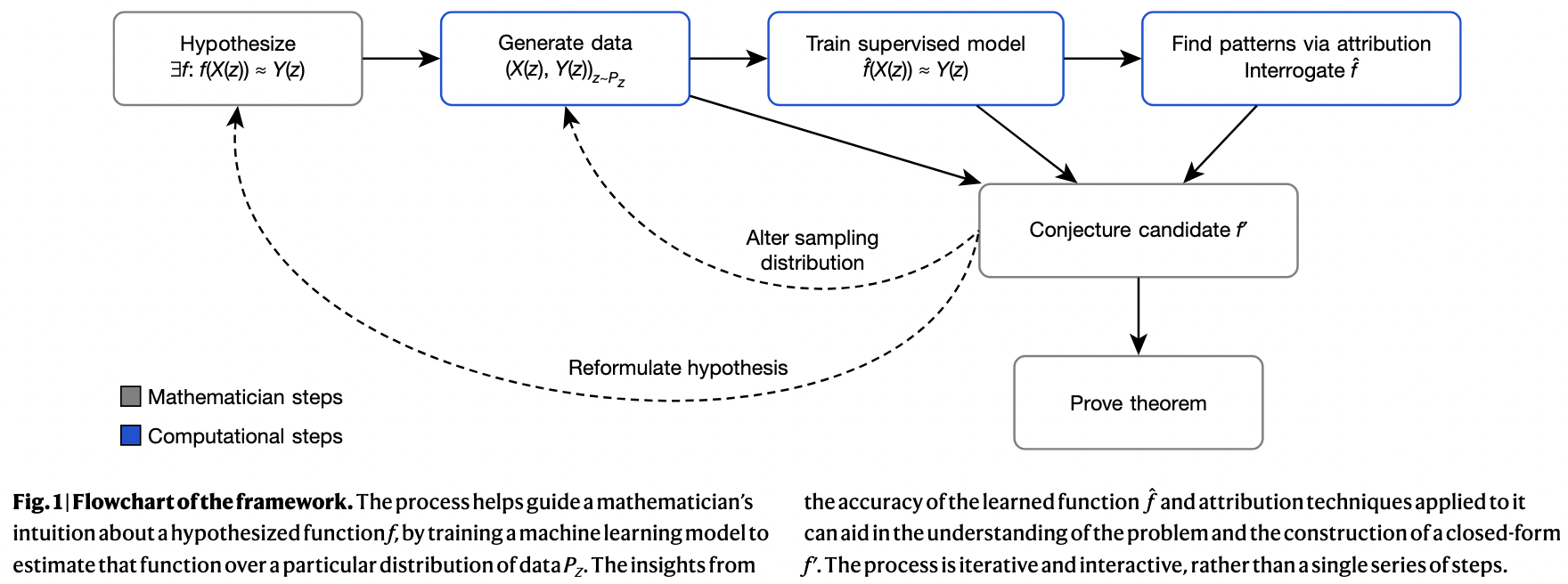

Last but not least, AI’s potential for mathematical discovery goes far beyond simply proving known theorems as it extends to the very generation of new conjectures and hypotheses. Back in 2021, before the rise of LLMs, the paper Advancing mathematics by guiding human intuition with AI was published in Nature11, demonstrating how deep learning can be leveraged for conjecture generation, which eventually led mathematicians to prove new results in knot theory and representation theory. This was one of the first successful instances of ML-assisted conjecture generation. The overall worklow is described below:

More recently, FunSearch was introduced in yet another Nature paper Mathematical Discoveries from Program Search with Large Language Models12, presenting a novel framework that pairs a pretrained LLM with a systematic evaluator in an evolutionary loop. Rather than searching directly for solutions, FunSearch explores the space of (Python) programs that generate solutions. This approach led to new state-of-the-art constructions in extremal combinatorics. The programs that FunSearch find are often interpretable, allowing mathematicians to understand and refine the discovered strategies.

Another notable method is PatternBoost which takes a different approach to automated discovery. It alternates between a local search phase—using classical algorithms to generate promising constructions—and a global phase in which a transformer is trained on the best examples to guide future searches. By blending symbolic search with neural generalization, it demonstrates how ML can help surface mathematical patterns that elude purely human or purely algorithmic approaches.

Just like mathematical information retrieval, these neuro-symbolic approaches feel far more aligned with the actual working style and needs of mathematicians: not just solving problems, but uncovering deep structure, drawing analogies, and generating insights.

If AI is to contribute meaningfully to Mathematics, it won’t be by simply outpacing us in proofs, but by becoming a tool for discovery, a companion in the search for understanding. Alongside formal languages, these systems stand to become assistants of abstraction, supporting mathematicians in uncovering structure, constructing proofs, and illuminating hidden patterns.

-

Remember Théâtre D’Opéra Spatial ? ↩

-

We say “sota” because we would feel too self-conscious where we to actually say “state-of-the-art”. ↩

-

Here are all the very basic undergraduate mathematic not even formalized in mathlib ↩

-

One point shy from a gold medal. Also a great example of DeepMind incentives, when the announcement was limited to a marketing publication. ↩

-

Kevin Buzzard again detailing his experience) in formalizing an IMO problem. ↩

-

On my limited set of tests, I found Claude 3.7 to do a great job at informalization. ↩

-

Full disclaimer, I currently work for Project Numina. ↩

-

Fun fact, one of the co-author Geordie Williamson, Professor of Mathematics at the University of Sydney was my PhD rapporteur. ↩

-

Because Google’s code for FunSearch is surprinsgly incomplete, a complete open source implementation can be found here. ↩